Strength and Weakness of Reading Data Analysis for 2nd Grader

- Inquiry

- Open Admission

- Published:

Subject field-specific strength and weaknesses of fourth-grade students in Europe: a comparative latent profile analysis of multidimensional proficiency patterns based on PIRLS/TIMSS combined 2011

Large-scale Assessments in Education volume 4, Commodity number:14 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

In 2011 the Progress in International Reading Literacy Report (PIRLS) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) were conducted at fourth grade in a number of participating countries with a shared representative sample. In this article nosotros investigate whether there are multidimensional proficiency patterns across the competency domains or not.

Methods

In order to derive proficiency patterns beyond the reading (PIRLS), mathematics and science (TIMSS) competence domains, latent profile analyses (LPA) of students' plausible values were conducted. For this, the grade iv student sample from 17 countries were combined and analyzed. The international reference model that resulted from this assay was and so applied with constraints to all 17 countries separately so that substantial comparisons between countries became possible. To describe and compare the differences between national profiles a classification arrangement was developed and practical to all countries' profile patterns.

Results

As a result of these international LPA 7 groups of learners were identified. The profiles were approximately equidistant and parallel. For all countries we find that achievement across domains can be explained by a general level of achievement rather than discipline-specific strengths or weaknesses of learners. However, subject-specific strengths and weaknesses can be identified but are—with the exception of Malta and Northern Republic of ireland—for most of the countries rather small. For only most half of the countries, a rather uniform blueprint of subject-specific strengths and weaknesses tin be found on all competence levels. The bailiwick itself varies betwixt countries. In the other countries high, intermediate and low achievers differ in their relative subject-specific strength and weaknesses.

Conclusions

The results propose that differences in average achievement in TIMSS and PIRLS should also on land level exist interpreted with caution. International comparative studies should further investigate potential reasons for the differences between countries.

Background

Results in reports of national and international large-scale cess studies are unremarkably contextualized with countries' achievement in specific domains compared against international benchmarks (Bos et al. 2012a, b; Martin and Mullis 2013). Nevertheless, crude comparisons—for case, which country has the highest proportion of students meeting the highest benchmark in mathematics or science or reading, or which country ranks beneath the international average in all three subjects—tin often be insensitive to the texture of within-state, and even between-state variation in accomplishment. For instance, how is achievement in one domain related to another? Practise the under-achieving students have specific strengths compared to high achievers? Do higher-achieving or lower-achieving students show similar patterns of strengths or weaknesses across countries? With this newspaper we aim to describe and compare achievement of Grade 4 learners between countries and across domain specific achievement by modelling multidimensional proficiency profiles making utilise of the combined datasets of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Written report (PIRLS) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Scientific discipline Study (TIMSS) 2011.

A comprehensive perspective on outcomes

Students' bookish competencies are the results of a complex interplay between factors located at the country, the school, the classroom, and the student level. A lot of these factors shape inter-individual differences in pupil achievement in a rather similar fashion (Bergold et al. 2016). This might be a possible explanation for the finding that students in countries reaching sure levels in ane achievement domain tend to reach similar results also in other domains (eastward.g., Martin et al. 2012; Mullis et al. 2012a, b).

Further, approaches to "interdisciplinary" or cross-subject education (Petersen 2000; Gudjons and Traub 2012) emphasize that a student understands his or her reality not contained within the bounds of one subject or another but, instead, across a gear up of applicable, interdisciplinary constructs (Lenzen 1996; Jonen and Jung 2007). This thought confirms the psychological perspective, which suggests that the development in competence domains is based on transferrable skills and dispositions common to all subjects (Weinert 1999). From this perspective, an individual's power to acquire is understood as a domain-general competence, which brings together in tandem a set of cerebral skills and strategies besides as prior knowledge and abilities. Regardless which perspective is taken, if learning occurs across domains (Baumert et al. 2000), information technology tin can be assumed that primary schoolhouse students' conquering of skills in reading, mathematics, and scientific discipline develops at least partly parallel to 1 some other (run across Schurig et al. 2015).

Empirical inquiry results back up the assumption that learning in 1 subject field is related to learning in some other, and hence multidimensional, mutually dependent distributions achievement patterns should be found. For example, the reading, mathematics, and science scores from PISA were constitute to inter-correlate from r = .75 to r = .81 (Reilly 2012) or even from r = .95 to r = .99 (Rindermann 2007). In TIMSS and PIRLS 2011, for the German sample the correlations were lower but still substantial, ranging from r = .54 to r = .74 (Bos et al. 2012a).

What these correlations suggest is that high or low achievement in one subject is highly related with high or low accomplishment in the others. Information technology as well gives evidence for further investigation of achievement as a multidimensional construct. Thus the question arises how such relationships can be modeled and further investigated in an international comparative context.

Profiles of country specific force and weaknesses in pupil achievement

Many studies making using from international big-calibration assessment have investigated and established well defined profiles of students within one specific content domain or subject (Lie and Roe 2003; Grønmo et al. 2004; Olsen 2005; Angell et al. 2006). These studies show that the investigation of proficiency profiles enhances the knowledge of differences between countries and therefor provide valuable knowledge for the comparisons of education systems. For example, Olsen (2005) models profiles to study cantankerous-state variations in the response patterns in mathematics achievement for students participating in PISA 2003. With this approach Olsen was able to distinguish a so-called Nordic profile from a profile for English-speaking countries. For science Olsen (2005) constitute show for a North-Westward European contour using science cognitive items from PISA 2003.

And so far, in all of these studies cluster analysis were performed based on the manifest item scores to derive domain-specific cantankerous-country differences in then-chosen item specific strengths and weakness inside a single accomplishment domain. It is far beyond the telescopic of this paper to discuss the methodical challenges that ascend when only the item responses of the students are used as the dependent variable instead of the plausible values (and vise versa). However it seems worth to study the question which profile solutions result when the plausible values instead of the item responses are used as the dependent variable. Besides, for investigations of profiles across accomplishment domains the multidimensional nature of the competencies domains should be taken into business relationship when a profile solution is derived because the dimensions are usually highly correlated (see above).

Using an approach based on the plausible values of the students for the PIRLS/TIMSS 2011 combined sample, Mullis (2013) calculates the proportion of 4th-grade students who meet depression and loftier international benchmarks in i, 2, or all iii of the competence domains by country. Mullis notes that, on the i paw, countries that accept big proportions of fourth-graders coming together the high international benchmark in all 3 domains are best equipping their students for later learning. On the other hand, if any given state has a relative modest proportion of students meeting the low international criterion in any given subject, these would be the students who are considered "left behind" to the extent that schools are failing to teach them the skills that support subsequently achievement. Combined with the information given in the International PIRLS/TIMSS-Reports (Martin et al. 2012; Mullis et al. 2012a, b; run into Table 1) on mean achievement and proportions of students reaching different International Benchmarks, it can exist institute that in x of the 17 EU-member countries participating in this study (Austria, Czech Democracy, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden), students seem to show a consequent field of study-specific weakness in mathematics. In contrast, in Ireland, Republic of lithuania, Malta, Northern Ireland and Portugal, students show a consequent subject-specific weakness in science. For Deutschland, a relative strength in reading is reported and for Romania a relative strength in scientific discipline. However, taking into account the differences in standard deviations for countries, it remains unclear to what extent these mean findings can exist generalized to the different groups of low or high achievers within the countries.

While a footstep in the management of describing how accomplishment looks across all domains and determining which countries are faring well at preparing the bulk of their pupils for more advanced learning, latent profile analyses (LPA) offer a different methodological approach that allows for the classification of cross-domain or multidimensional proficiency profiles within and across countries. In other words, latent profile analyses of achievement allow to classify groups of students beyond those who are "well equipped" or those "left behind." These profiles, in plow, can be not only evaluated in terms of the quality of the selected classifications but too analyzed according to their subject-specific strengths and weaknesses as well equally co-ordinate to their relationships with social groundwork characteristics (Schurig et al. 2015).

To this end, Bos et al. (2012a, b) model latent profiles of student accomplishment in reading, mathematics, and science for 4th-form students in Germany. The authors plant seven invariantly rank-ordered profiles based on the similarity of students' cross-domain achievement then further studied relationships with background variables, such every bit gender, cultural and socioeconomic characteristics (Bos et al. 2012a, b). Gender differences only occurred in the grouping of the very high achieving students, as significantly more than boys than girls were found in this group. In terms of cultural and socioeconomic characteristics, all seven proficiency profiles were distinguishable, and a close relationship between achievement and socioeconomic groundwork was observed. In other words, at least in Germany, lower-achieving students across all domains look different in their social groundwork from higher-achieving students.

In this paper we apply this same procedure to 17 European countries that participated in TIMSS/PIRLS combinded in a pooled sample of 4th-graders. We identify proficiency profiles across the countries. We then fit this international European model with constraints to all 17 countries separately to compare the multidimensional proficiency profiles between countries. We then analyze the derived profiles in more than particular to identify discipline-specific strengths and weaknesses within and beyond profiles. These country-specific patterns are then compared across countries and the relationships to well-known results of educational research are shown. Hence, this paper aims to respond the following main questions: (1) How many profiles describing achievement patterns of students in the participating EU countries can be separated? (ii) What is the distribution of learners assigned to these profiles? (3) How are students distributed beyond the profiles with regard to their background characteristics, such equally parent educational groundwork, language spoken at home, positive attitude towards learning and domain-specific self-concepts? (4) How are high- and low-achieving students in unlike European countries distributed? (5) Are there substantial differences in the multidimensional proficiency profiles across countries? (6) Can differences in the domain-specific strengths and weaknesses betwixt countries be observed?

Methods

Sample

We used representative data from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2011 and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2011. Both studies are ordinarily conducted independently of each other, executed in different cycles and focusing on different outcomes. In 2011, however, the studies were in some countries conducted mutually, testing students in mathematics, science, and reading.

Overall, 37 countries and benchmark participants participated in PIRLS/TIMSS combined with samples of fourth graders. We used the data from grand = 17 countries that both took part in TIMSS/PIRLS 2011 combined and were members of the European Union when data drove took identify (i.e., Austria, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Republic of ireland, Italy, Republic of lithuania, Malta, Northern Ireland, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden) as these countries follow a common strategic educational framework (Education and Training 2020 program; European Commission 2015). The 17 samples resulted in a full sample of n = 74,868 4th form students from 2704 schools. Due to the sampling process implemented in PIRLS and TIMSS, information technology was ensured that the students in the dissimilar countries were all comparable regarding their age and their corporeality of schooling. All countries practical a strict sampling process to let analyses of nationally representative data. Sample selection was strictly monitored in every state to preserve high quality sampling standards (for more details regarding the sampling process come across Martin and Mullis 2012).

Data

The combined international data sets of fourth form students of all countries that participated in TIMSS/PIRLS 2011 are used. Footnote 1 From these data sets, the state-specific data files ASG***B1 and ASH***B1 are used, where *** stands for a country specific lawmaking, ASG are the pupil background information files, and ASH are the corresponding home background data files. These data files are offset merged beyond information file sources and then combined across countries. For the multidimensional proficiency profiles of the students from the 17 countries, the plausible values in reading achievement, mathematic accomplishment and science achievement (which are part of the ASG***B1 data sets) are analyzed. This scaling procedure differs from the one used for the international reports (Mullis et al. 2012a, b; Martin et al. 2012) as it preserves the correlational structure beyond the three subjects (multi dimensional model: for a detailed description of the scaling procedure and the use of plausible values, come across Foy 2013). Each achievement scale is gear up to its own metric with an international mean of 500 and a standard difference of 100. The distribution of the students beyond countries together with sample statistics about characteristics of the students is shown in Table 2.

Latent profile models

For deriving the multidimensional proficiency profiles of the fourth class students, latent profile analyses were conducted (Lazarsfeld and Henry 1968). In this method, the multidimensional marginal distribution of accomplishment values of all students is separated into distinct conditional distributions, which are assumed to mix up to the marginal distribution (thus this procedure is also known as mixture model). The distinct provisional distributions are called latent profiles, and these are normally characterized by their conditional means on the dimensions of the multidimensional distribution and past the percentage of students forming the profiles. However, as they are (at to the lowest degree theoretically) space with many possible separations of the marginal distribution into conditional distributions, and considering the (marginal equally well as conditional) distributions are probabilistic in nature, the derived number of latent profiles and the consignment of the students to these profiles are probabilistic as well. Thus, for judging which of these different possible separations of the marginal distribution into mixture distributions should exist called, various fit criteria are bachelor. In this study, the Akaike information benchmark (AIC; Bozdogan 1987), and the sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (CBIC; Schwarz 1978) are used. Smaller values of these criteria indicating a better fit of the assumed mixture. In improver, the nomenclature error rate, entropie and pseudo-reliability for the concluding solution are calculated.

Using latent contour analysis, a four-footstep approach is established. In the first stride, the total sample of students (due north = 74,868) were separated into ii to eight mixtures and the resulting vii different mixture distributions are compared based on the fit criteria (Model one; international model). Afterward deciding for a physical mixture out of these seven mixtures, the conditional ways of the profiles are calculated.

In the 2nd step, these conditional ways are introduced as fixed parameters in national latent profile assay. That is, the country specific multidimensional marginal distribution of 4th class educatee'south accomplishment values are separated into mixture distributions, in which the number of mixtures and the ways of the mixtures are fixed at the values from the international model (Model 2; state specific models with fixed means). Thus, how well the international model fits the national distributions could be assessed, and the probability distribution of the students beyond the profiles (that is, the percentage of students forming the profiles) could exist estimated.

In the third pace, the national models are again fitted, but this fourth dimension the ways of the conditional distributions are gratuitous parameters (Model iii; country specific models with free ways). This allows for different contour patterns across countries.

In the terminal step, the so-chosen validation step, Model 1 was again fitted, simply this time fixing the number of profiles and the ways on the results of Model 1 and with inclusion of students' groundwork characteristics. Hence, the relationship between the derived international profiles and the background characteristics of the students could be estimated and compared.

Indicators for subject-specific strengths and weaknesses

The means of the profiles from Model one and Model 3 are used to derive four different indicators of subject-specific strengths and weaknesses. For the first indictor, three comparisons of the provisional achievement mean values given profile 10 (10 = 1, …, k; k number of assumed profiles) are performed for each model (and country) separately. The showtime comparing involves the deviation between reading and mathematics achievement, the second comparison involves the departure between reading and science accomplishment, and the 3rd comparison involves the difference between mathematics and science achievement.

A subject-specific force or weakness for subject Y in profile X is designated if the respective comparison results in a difference from at least ten points, which is the boilerplate standard error of the conditional hateful beyond profiles and achievement domain given Model 1. Because at that place are three competence domains from which none could be the strongest, or from which merely one could exist the strongest, or in ordered pairs or ordered triples the strongest and the weakest, the procedure for designating bailiwick-specific strengths and weaknesses could result in xvi possible subject-specific achievement combinations or patterns within profiles, from which 13 combinations convey different meanings: (No differences (OOO), Relative strength in Reading (R); Relative strength in Reading and Mathematics (RM & MR, reported every bit RM), Relative strength in Reading, then in Mathematics so in Science (RMS), Relative forcefulness in Reading and Scientific discipline (RS & SR, reported as RS), Relative strength in Reading, and then in Science and and then in Mathematics (RSM), Relative strength in Science (S), Relative forcefulness in Scientific discipline, then in Reading and then in Mathematics (SRM), Relative force in Science, then in Mathematics and then in Reading (SMR), Relative strength in Mathematics (M), Relative forcefulness in Mathematics and Science (MS & SM, reported as MS), Relative strength in Mathematics, and so in Scientific discipline and then in Reading (MSR) and Relative strength in Mathematics, then in Reading and then in Science (MRS).

The second indictor (which nosotros term, "mean within profile heterogeneity") is the boilerplate deviation between achievement domains (given profile 10) across profiles. This indicator could exist interpreted as the average heterogeneity of achievement across subjects and profiles. Hence, a high value on the mean inside profile heterogeneity indicating a large subject-specific force or weakness, a value of zippo indicates no measureable subject-specific strength or weakness.

For the tertiary and quaternary indicators, the difference between the mean of the highest profile and the lowest profile for each domain is calculated. To calculate the 3rd indicator (mean-between contour variance), these 3 differences are averaged. For the 4th indicator (mean-between profile heterogeneity), the average absolute differences between this means (e.g. average deviation) is estimated. Hence, the third indicator designated the overall distance between the lowest and highest contour across domains. A value of zero indicates perfect overlapping of the profiles. The fourth indicator could be interpreted as the degree to which the subject-specific differences beyond profiles are constant beyond domains. A value of null on this indicator indicates that there are no subject-specific profile differences.

Analytic strategy

Considering plausible values for the achievement domains are used, all analyses in this study were performed 5 times (for each plausible value once). The results of these analyses were combined co-ordinate to the formula by Rubin (1987). "Senwgt" is used as the weighting variable for the international model, which sums up to a total sample size of students of 500 for each country. This produces equal weighting of the countries in the international profile model. For the country specific profile models, "houwgt" is used, which sums upwards to the observed sample size of students for every country. Unless otherwise stated, all the analyses for this paper were generated using Mplus Version 7.11 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) in combination with the total information maximum likelihood approach.

Results and discussion

Latent contour models

Our kickoff research question asks how many profiles describe the achievement patterns of students the European union-participants all-time. To investigate the data for the full sample representing all primary school students attention schools in Europe (n = 74,868) were separated into two to eight mixtures. Table three displays the fit criteria for the international latent profile model. As tin be seen, the BIC and CAIC consistently decrease as the number of causeless mixtures increases. Still, since the changes between the model with seven and eight profiles was very depression, and because the proportion of students that could be assigned to the profiles with 8 mixtures is very low for some conditional distributions, a latent contour model with seven mixtures is chosen.

The proportion of students that can be assigned to the seven profiles and the provisional means of the seven mixtures are shown in Tabular array 4. The contour ways on the achievement domains progressively increase from profile 1 to profile 7: thus, no cross-nested structure for the profiles can exist observed. This suggests that the students tin can mainly be separated by dissimilar achievement levels on all domains simultaneously, rather than differentiation with respect to subject-specific strengths or weaknesses. Yet, as shown afterward in the results, a more detailed look at the profiles reveals separable groups of students with relative subject-specific strengths and weaknesses.

Afterwards applying the international contour model in each land separately, while holding the means constant, the proportion of misclassified students (nomenclature error), the Entropie and the Pseudo-reliability can exist estimated. The resulting values bespeak an acceptable fit of the model in nigh countries (see Table 5). All the same, the assignment of the students from the sample of Romania and Malta is non as straightforward. Specifically, at least a quarter of the students in these countries could non be assigned reasonably well into the international profile model. Nevertheless, a transfer from the international profile model to the land specific distributions of students' achievement values is possible without further restrictions.

Multi-competence profiles of European fourth-graders

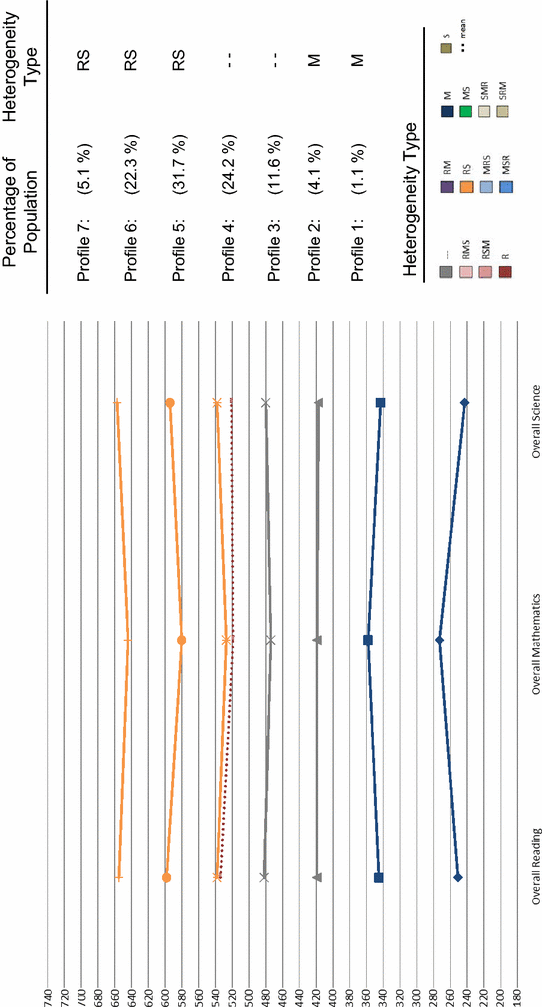

Our second enquiry question aims at describing achievement of 4th-form learners in Europe across subjects. Figure i shows the proportions of students in each of the multidimensional proficiency profiles. The profiles are color coded according to the discipline specific strengths and weaknesses students show at the unlike levels of competencies (see Table 8). Codes of like colour shades (e.k. "reds" versus "blues") betoken similarity between the bailiwick-specific strengths and weaknesses.

International achievement profiles of fourth-grade students in Europe in reading, mathematics, and science

It tin be seen that the profiles are invariantly rank ordered. Well-nigh 60 % of all students are assigned to profiles 5, 6 and vii, which depict cantankerous-subject functioning to a higher place the subject-specific European averages (reading: 534; mathematics: 519; scientific discipline: 521). For these profiles, relative strengths in reading and scientific discipline become apparent. 5.one % of all students are assigned to profile 7. These students show, with an average of 644 points for mathematics, 655 points for reading and 657 points for science, excellent results higher up the PIRLS/TIMSS Advanced International Benchmarks in all subjects. For profiles 3 and four, which describe the cross-subject field accomplishment patterns of 35.eight % of all students, no relative strengths can be observed. For profiles 1 and 2, which describe achievement below the PIRLS/TIMSS Low International Benchmarks, a relative strength in mathematics is observable. All the same, only 5.two % of all students can be assigned to these profiles.

Relationship betwixt educatee traits and the European multi-competence proficiency profiles

Our third enquiry question aims at describing the relationship between student traits and the European multi-competence proficiency profiles. Tables half dozen and 7 show the proportions of students assigned to the unlike profiles past socioeconomic and cultural characteristics and family language too as indicators for attitudes towards learning and self-concept.

Looking at the distribution of different profiles past socioeconomic and cultural characteristics and family unit language as well as indicators for attitudes towards learning and cocky-concept, it can be seen that the modeled profiles clearly distinguishes between students with diverse traits. Students from families with relatively high socioeconomic and cultural capital letter are over represented in higher achieving profiles, students from homes with less educational resources or an immigrant background are overrepresented in lower achieving profiles. The profiles are also clearly distinguishable by attitude toward learning and cocky-concept.

Proficiency profiles of students in dissimilar European countries

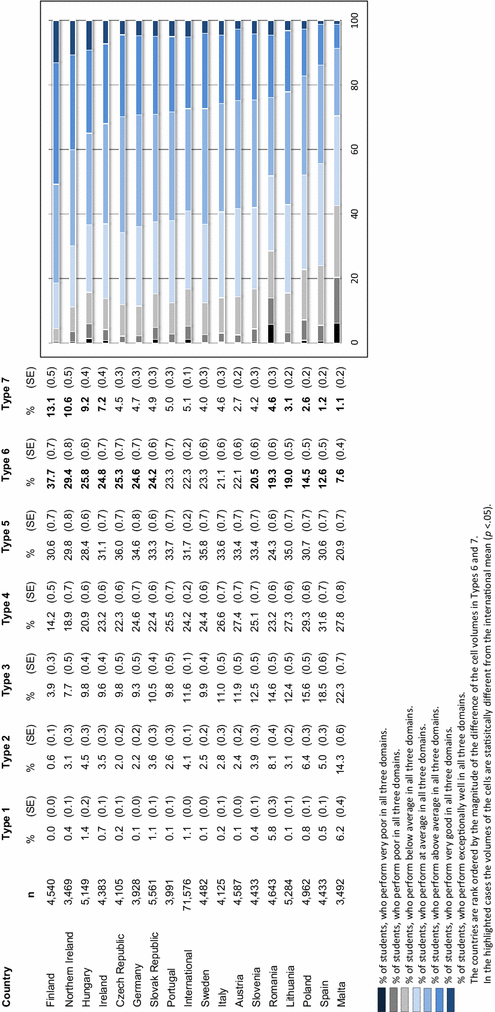

Our fourth inquiry question aims at a European comparison of proportions of high and low achieving students in each of the multidimensional proficiency profiles. For this, the European model was practical for all countries with stock-still number of latent classes merely variation of latent means. This provides information about the distribution of achievement profiles in and between countries. In Fig. ii, these resulting proportions are shown for all profiles by country and for the European model. The results are presented in descending gild according to the percentage of students in profiles half-dozen and 7.

Proportions of students in each of the multidimensional proficiency profiles by country

Information technology can be seen that, with the exception of Finland and Northern Ireland that accept larger proportions of high achievers, in all countries about half of the students are assigned to profiles 4 and 5. The proportions of students in the profiles that draw the beyond subject performance of the high and low achievers vary essentially betwixt countries: Republic of finland (thirteen.1 %), Northern Ireland (10.6 %), Hungary (9.2 %) and Ireland (7.2 %) show the largest percentages of students who show fantabulous results in all iii subjects (profile seven), whereas in all other countries, less than 5 % of all students prove comparable results. Taking a wait at the lower achieving profiles, Republic of malta (twenty.5 %), Romania (13.nine %), Poland (7.ii %), Hungary (5.9 %) and Spain (5.5 %) show the largest percentages of students in profile 1 and ii. In all other countries, the percentage of these very low performing students is beneath 5 %.

Frequencies of relative bailiwick-specific achievement patterns

Our fifth inquiry question aims identifying domain-specific strengths and weaknesses between countries. For this, the country-specific achievement profiles (north = 119) were coded according to the relative subject-specific achievement patterns (for state-specific coding see Table 10; Additional file 1: Appendix S1). Table 8 shows the frequencies of relative subject field-specific accomplishment patterns across all European countries in total and for the highest (contour half dozen–seven) and lowest (contour 1–three) achieving profiles.

As shown in Table 8, for about 91 % of all profiles across all European countries, a subject-specific strength or weakness for one or two subjects can exist observed, when 10 point within profile achievement difference is considered substantial. Footnote 2 11 % of all profiles describe a relative strength in reading, 22 % a relative force in mathematics and 23 % a relative strength in science. The almost common profiles draw a comparable strength in reading and science (RS, 27 %); a relative forcefulness in science, where the reading competences exceeds mathematics competencies (SRM, xiii %), a relative singular forcefulness in mathematics (One thousand, 13 %). A comparison of codes between profiles shows that more than 2 thirds of all profiles describing high and fantabulous accomplishment across the subjects (profiles six and 7; 74 %) but only about half of the profiles describing depression accomplishment (profiles i–3; 47 %) prove a relative strength in science and/or reading (SRM, RS, R, S, RSM). It tin also be plant that, whereas merely 18 % of all patterns found for profiles half-dozen and 7 show a relative strength for mathematics, most 43 % of the profiles 1–three show a respective accomplishment pattern for the depression achievers. For the high achievers, in 71 % of all profiles, a forcefulness in science becomes apparent, but only for 31 % of the profiles describing low achievement. Furthermore, the contour showing a singular force in mathematics is in iii of 4 cases establish among the profiles 1–3. Also, the contour showing a singular strength in reading is almost commonly found amid the profiles describing low achievers.

Similarities and differences in relative field of study-specific achievement patterns between countries

Our sixth research question aims at identifying similarities and differences in relative subject-specific accomplishment patterns between countries. To describes and compare the within-land differences of achievement profiles in terms of the size of achievement differences between subjects as well every bit the bigotry of the profiles between competence levels and subjects different indicators were divers (see section on indicators for subject area-specific strengths and weaknesses).

In a 2d footstep, the distribution of discipline-specific achievement patterns by state was analyzed and rated according to the within-country contour heterogeneity. Here, the within-country profile heterogeneity was considered "low" when at to the lowest degree five out of seven profiles followed the aforementioned pattern of subject-specific strengths and weaknesses, "rather low" if at that place is a more than diverseness of codes but the plant patterns evidence an equal bureaucracy of subjects, and "high" when at that place is a diverseness of codes and rather diverse bailiwick-specific strengths and weaknesses.

Every bit shown in Table 9, countries differ according to their average heterogeneity of achievement across subjects and profiles (mean within profile heterogeneity). Hence, in some countries, subject specific strengths and weaknesses are more distinct than in others: Germany (xi), Republic of hungary (xi) and Slovenia (eleven) show the everyman average differences among domains beyond all seven achievement profiles. Here, the achievement results across the domains within a profile are rather homogeneous and simply minor specific strengths and weaknesses are observed. In contrast, in Malta (40), Northern Ireland (29), Sweden (21) and Poland (20), subject-specific strengths and weaknesses tin exist observed much more frequently.

The column headed "Average of conditional domain specific betwixt profile variance" shows the overall distances betwixt the lowest and highest profile across domains (shown in Table 10). The values between 299 and 463 indicate that in all countries, the profiles overall cover quite a big range of different achievement levels. Interestingly, in more than than one-half of the countries, the largest divergence between the mean of the highest profile and the hateful of lowest contour can be institute for mathematics whereas simply for two countries (Malta and Deutschland), the largest between-contour variance can exist found for reading.

Also the caste to which the domain-specific differences across profiles are constant across domains is shown in Tabular array 9 (hateful between-profile heterogeneity). Republic of hungary (eight), Lithuania (17) Ireland (xviii), Republic of finland (21) and the Czech Republic (22) show the smallest differences among the European countries, whereas in Republic of malta (83), Sweden (53), Romania (46) and Spain (41) the biggest differences tin be found.

Every bit shown in Table 10 the distributions of achievement patterns vary considerably between countries. Looking at the distributions within countries, seven countries exhibit low or rather depression heterogeneity, whereas the ten other countries exhibit loftier. For Finland, Republic of lithuania, Northern Ireland and Poland, the state-specific achievement profile across subjects follows the same blueprint at all levels of competencies. Simply contour 1 diverges, though it represents the accomplishment of ane.0–2.6 % of learners at the lowest end of the calibration. Here, no differences between the subjects could exist found. Withal, the profiles do differ betwixt countries: In Republic of finland, students at all achievement levels show relative strength in science followed past reading. In Lithuania, students at all levels are stronger in mathematics, whereas scientific discipline is a articulate weakness in Poland and in Northern Republic of ireland in Hungary, for the high achievers (contour 7 and 6), a relative strength in science followed by reading is observed, whereas for all other profiles, students perform equally well in science and reading. For Ireland a relative strength in reading followed by mathematics. In Italy, a relative strength in reading followed by science is visible. In both the Czech Republic and Sweden a higher degree of heterogeneity a relative strength in science followed by reading can be found.

For countries with a loftier caste of within country profile heterogeneity, two groups can be distinguished: in Republic of austria, Germany, Malta, Slovenia and Spain, low performers show a relative force in mathematics whereas high achievers bear witness a relative force in reading and scientific discipline. In the Slovak Republic and Romania, a relative force in science is found for the loftier achievers whereas low achievers bear witness a relative strength in reading.

Conclusions

In public debates, students are oft described equally learners with specific strengths or weaknesses in one specific learning area. However, several studies show that achievement results in mathematics, reading literacy and science are highly correlated. In this article we aim at exploring multidimensional proficiency patterns of fourth-grade students in Europe across achievement results in reading, mathematics and science. The joint cess of PIRLS-2011 and TIMSS-2011 in a representative sample of grade-4 students provides a unique dataset to discover common structures across achievement domains and groups of learners with unlike achievement patterns.

To generate an accomplishment typology to describe patterns across the 3 domains, a latent profile analysis (LPA) was performed on the plausible values of the students overall and by country. All models show a reasonable fit and, in almost all countries, at least 75 % of the students tin be reasonably described by the institute achievement profiles. These profiles provide an informative approach to identifying and comparison proportions of learners at unlike levels of competences. Our findings on the proportions of depression- and high-achieving students are consistent with the findings from Mullis (2013). An additional force of the profiles is that they can be farther explored co-ordinate to their relationship(s) to different pupil traits. Here, we discover that the profiles were highly distinguishable with regard to their groundwork characteristics and consistent with the findings reported in the international reports. This supports the merits that the profiles allow a useful clarification of variation betwixt countries on a singular issue.

In addition, modeling by accomplishment profiles within countries allows to investigate patterns of achievement by subject-specific strengths and weaknesses. Based on the derivable patterns, a comparing betwixt subject–specific achievement patterns beyond different proficiencies tin can reveal differences.

Concerning subject field-specific strengths and weaknesses for both the European too as in the country models, we observe no cross-nested structure for the profiles. Hence, achievement beyond domains can be rather explained by a full general level of achievement than subject-specific strengths or weaknesses of learners which advise that the didactics systems of the analyzed member states of the European Marriage are doing a good job in providing balanced teaching for their students regardless the contour level. However, some bailiwick-specific strengths and weaknesses can be identified but these are—with the exception of Malta and Northern Ireland—for most of the countries rather small. For the European model, it tin can be shown that those students who perform above average have a relative forcefulness in reading and science, where depression-performing students bear witness a relative strength in mathematics. Withal, it can too exist shown that this international blueprint only represents the patterns of Republic of austria, Germany, Malta, Slovenia and Espana rather well. For nearly one-half of the countries, a rather uniform pattern of subject area-specific strengths and weaknesses tin can exist found on all competence levels. For these countries, it can exist stated that they are educating their all their students more successfully in one or 2 subjects than in the other(due south). The subject field itself varies between the countries. The country profiles were further distinguished according to their degree of within- and betwixt-profile heterogeneity. Here, for countries with a relatively larger proportion of high achievers (Hungary, Republic of finland, Czech Republic, Northern Ireland), the same pattern of strengths and weaknesses tin can be identified for all profiles and—with the expectation of Northern Ireland—the degree of the differences inside profiles is rather small. This and the finding that profiles that describe a singular forcefulness in mathematics or reading are overrepresented among the depression achievers, might suggest that a successful education for all with a sufficient number of loftier-achievers requires a solid educational basis in all subjects. Withal, the results as well support the finding that high achievers show relative forcefulness in science and to a lesser extent in reading.

In society to study various within- and betwixt-country-differences in proficiency patterns we classified a 10 point inside-profile difference in achievement between domains every bit substantial. Nosotros cull this criterion because 10 points is exactly the boilerplate standard error of the (provisional) mean across profiles and achievement domain. Thus, only differences at or above 1 (average) standard error are considered equally relevant in this paper. Also this criterion is somewhat capricious: differences less than ten points should surely non exist seen as relevant taken the sampling fault (as expressed by the standard mistake) of the plausible values (and the profile solutions) into account. Therefore the x points can be seen every bit a lower threshold for comparing relative subject field-specific strength and weakness. With this lower threshold, near 9 out of x profiles where considered to reveal a bailiwick-specific strength or weakness. If a higher threshold is used (for example differences at or to a higher place two standard errors) then still 68 % of all profiles would have been considered to reveal a subject area-specific strength or weakness. That is, the reported results in this paper volition non change considerably fifty-fifty when a college threshold is used to derive subject-specific forcefulness or weakness. Withal further inquiry is needed to investigate the sensitivity of the herein derived test statistic with respect to different threshold criterions.

In addition the presented results on within-and between-countries differences with regard to subject field-specific strength and weaknesses should not be over interpreted. Withal from an international comparative perspective it might be of interest to further empathise why some countries bear witness rather homogenous patterns of strengths and weaknesses for all students regardless of the proficiency levels, whereas in other countries the subject-specific strengths and weaknesses differ betwixt low and high-achieving students.

What could be further enquiry directions? Generally, it volition be highly challenging to develop a coherent framework for deriving useful indictors that explains subject-specific strengths and weakness within profiles, between profiles and across countries. Amongst others, such indicators should be derived from input factors (due east.1000. instructional time) and process factors (e.thousand. cross-cultural differences in emphasis of subjects). The question arises whether research traditions from economics could be helpful here to. From a statistical point of view, it seems highly challenging to introduce the classes (schools) as a cluster cistron in the mixture models, as they are commonly only small-scale samples within the classes (schools). Nevertheless, the correlation structure of large-scale assessment samples calls for such techniques. In improver, explaining the variance of profiles inside a country and beyond schools could provide highly valuable information. Furthermore, the extensions of the latent mixture model to the subscales of PIRLS (reading purposes; comprehension processes) and TIMSS (content domains; cognitive demands) seem worth consideration. Finally, the interdependent relationship betwixt the well-established benchmarks and the newly adult proficiency profiles could be farther studied.

Notes

-

When a 20-indicate-difference is considered substantial 68 % of all profiles show a relative field of study-specific force or weakness for one or two subjects. When a thirty-bespeak-difference is considered substantial just 15 % of all profiles show a relative bailiwick-specific force or weakness for 1 or two subjects.

Abbreviations

- LPA:

-

latent profile analysis

- PIRLS:

-

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study

- TIMSS:

-

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

References

-

Angell, C., Kjærnsli, Grand., & Lie, S. (2006). Curricular and cultural furnishings in patterns of students' responses to TIMSS science items. In Due south. J. Howie & T. Plomp (Eds.), Contexts of learning mathematics and science: lessons learned from TIMSS (pp. 277–290). London: Routledge.

-

Baumert, J., Klieme, E., Neubrand, M., Prenzel, One thousand., Schiefele, U., Schneider, W., et al. (2000). Die Fähigkeit zum Selbstregulierten Lernen als fächerübergreifende Kompetenz. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institut für Bildungsforschung.

-

Bergold S, Wendt H, Kasper D,Steinmayr R. (2016). Academic Competencies: Their Interrelatedness and Gender Differences at Their High Terminate. Journal of Educational Psychology 108(six)

-

Bos, Westward., Wendt, H., Ünlü, A., Valtin, R., Euen, B., Kasper, D., et al. (2012b). Leistungsprofile von Viertklässlerinnen und Viertklässlern in Deutschland [Achievement profiles of fourth-graders in Germany]. In W. Bos, H. Wendt, O. Köller, & C. Selter (Eds.), TIMSS 2011. Mathematische und naturwissenschaftliche Kompetenzen von Grundschulkindern in Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich (pp. 269–301). Münster: Waxmann.

-

Bos, W., Wendt, H., Ünlü, A., Valtin, R., Euen, B., Kasper, D., & Tarelli, I. (2012a). Leistungsprofile von Viertklässlerinnen und Viertklässlern in Deutschland Deutschland [Achievement profiles of fourth-graders in Germany]. In W. Bos, I. Tarelli, A. Bremerich-Vos, & K. Schwippert (Hrsg.), IGLU 2011. Lesekompetenzen von Grundschulkindern in Frg im internationalen Vergleich (pp. 227–257). Münster [u.a.]: Waxmann.

-

Bozdogan H. (1987). Model selection and Akaike'due south Information Criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika 52 (three):345–370.

-

Byrnes, J. P., & Miller, D. C. (2007). The relative importance of predictors of math and scientific discipline achievement: an opportunity-propensity analysis. Gimmicky Educational Psychology, 32, 599–629. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.09.002.

-

Chung, 1000. K. H. (2015). Socioeconomic condition and academic achievement. In J. D. Wright (Series Eds.) & C. Byrne, P. Schmidt, & C. McBride-Chang (Vol. Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences: pedagogy (pp. 924–930). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

-

European Commission. (2015). Strategic framework—educational activity and preparation 2020. http://world wide web.ec.europa.eu/education/policy/strategic-framework/index_en.htm.

-

Foy, P. (2013). TIMSS and PIRLS 2011 user guide for the fourth form combined international database. Chestnut Loma: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Middle, Boston College.

-

Grønmo, Fifty. South., Kjærnsli, M., & Lie, S. (2004). Looking for cultural and geographical factors in patterns of response to TIMSS items. In C. Papanastasiou (Ed.), Proceedings of the IRC-2004 TIMSS (Vol. 1, pp. 99–112). Nicosia: Cyprus Academy Printing.

-

Gudjons, H. & Traub, Due south. (2012). Pädagogisches Grundwissen. Überblick—Kompendium—Studienbuch (UTB Pädagogik, Bd. 3092, 11., grundlegend überarb. Aufl). Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

-

Jonen, A. & Jung, J. (2007). SINUS-Transfer Grundschule Naturwissenschaften Modul G 6: Fächerübergreifend und fächerverbindend unterrichten, IPN. Zugriff am 05.03.2015. Verfügbar unter. http://www.sinus-transfer.uni-bayreuth.de/fileadmin/MaterialienIPN/G6_gesetzt.pdf.

-

Kellaghan, T. (2015). Family and schooling. In J. D. Wright (Series Eds.), C. Byrne, P. Schmidt, & C. McBride-Chang (Vol. Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences: education (pp. 751–757). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

-

Lazarsfeld, P. F., & Henry, N. West. (1968). Latent structure analysis. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

-

Lenzen, D. (1996). Handlung und Reflexion. Von pädagogischen Theoriedefizit zur reflexiven Erziehungswissenschaft. Weinheim: Beltz.

-

Lie, S., & Roe, A. (2003). Unity and diversity of reading literacy profiles. In Due south. Prevarication, P. Linnakylä, & A. Roe (Eds.), Northern lights on PISA (pp. 147–157). Oslo: Department of Teacher Educational activity and School Development, University of Oslo.

-

Martin, 1000. O., & Mullis, I. Five. S. (Eds.). (2012). Methods and procedures in TIMSS and PIRLS 2011. Chestnut Hill: TIMSS & PIRLS International Report Center, Boston College.

-

Martin & Mullis (2013). TIMSS and PIRLS 2011: human relationship among reading, mathematics and science accomplishment at the fourth form. Implications for early learning. Chestnut Hill: International Study Eye, Lynch School of Pedagogy, Boston College.

-

Martin, M. O., Mullis, I. V. S., Foy, P., & Stanco, G. G. (2012). TIMSS 2011 international results in science. Chestnut Hill: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College.

-

Mullis, I. V. Southward. (2013). Profiles of achievement across reading, mathematics, and science at the 4th class. In Grand. O. Martin & I. Five. Southward. Mullis (Eds.), TIMSS and PIRLS 2011: relationships amid reading, mathematics, and science achievement at the quaternary grade—implications for early learning. Chestnut Loma: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College.

-

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, Thou. O., Foy, P., & Arora, A. (2012a). TIMSS 2011 international results in mathematics. Chestnut Colina: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College.

-

Mullis, I. Five. S., Martin, Thou. O., Foy, P., & Drucker, Grand. T. (2012b). PIRLS 2011 international results in reading. Anecdote Colina: TIMSS & PIRLS International Written report Center, Boston College.

-

OECD. (2014). PISA 2012 results: What students know and can exercise: pupil operation in mathematics, reading and science (Vol. 1, revised ed.). OECD Publishing.

-

Olsen, R. V. (2005). An exploration of cluster structure in scientific literacy in PISA: evidence for a Nordic dimension? Nordina, 1(1), 81–94.

-

Petersen, W. H. (2000). Fächerverbindender Unterricht. Begriff—Konzept—Planung—Beispiele; ein Lehrbuch (EGS-Texte, 1. Aufl). München: Oldenbourg.

-

PISA Konsortium. (2004). PISA 2003. Der Bildungsstand der Jugendlichen in Deutschland : Ergebnisse des zweiten internationalen Vergleichs. Münster: Waxmann.

-

Prenzel, M., Sälzer, C., Klieme, East., & Köller, O. (Eds.). (2013). PISA 2012. Fortschritte und Herausforderungen in Deutschland. Münster: Waxmann.

-

Reilly, D. (2012). Gender, culture, and sex activity-typed cognitive abilities. PLoS ONE, vii(7), e39904. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039904.

-

Rindermann, H. (2007). The chiliad factor of international cognitive ability comparisons: the homogeneity of results in PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS and IQ-tests across nations. European Journal of Personality, 21, 667–706. doi:10.1002/per.634.

-

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

-

Schwarz G. (1978). Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(two), 461–464.

-

Schurig, M., Wendt, H., Kasper, D. & Bos, W. (2015). Fachspezifische Stärken und Schwächen von Viertklässlerinnen und Viertklässlern in Frg im europäischen Vergleich. In H. Wendt, T. C. Stubbe, K. Schwippert & W. Bos (Hrsg.), 10 Jahre international vergleichende Schulleistungsforschung in der Grundschule. Vertiefende Analysen zu IGLU und TIMSS 2001 bis 2011 (pp. 35–54). Münster: Waxmann.

-

Weinert, F. Due east. (1999). Konzepte der Kompetenz. Paris: OECD.

-

Wendt, H., Kasper, D. & Bos, W. (2014). Multi-competence proficiency profiles of grade four learners—a European comparison based on TIMSS/PIRLS 2011 combined. In Presentation held at the European conference on educational enquiry (ECER) 2014 in Porto.

Authors' contributions

HW: conception and design, conquering of data & drafting the article; DK perfomed the analysis. Both authors interpretated of data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this article

Wendt, H., Kasper, D. Discipline-specific force and weaknesses of 4th-form students in Europe: a comparative latent profile assay of multidimensional proficiency patterns based on PIRLS/TIMSS combined 2011. Large-scale Appraise Educ 4, xiv (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-016-0026-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s40536-016-0026-2

Keywords

- Multidimensional proficiency

- Main school

- Europe

- PIRLS/TIMSS 2011 combined

Source: https://largescaleassessmentsineducation.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40536-016-0026-2

0 Response to "Strength and Weakness of Reading Data Analysis for 2nd Grader"

Post a Comment